Through each of these tales runs a traditional Japanese ghost story. It's as if the world of modern Japan is not only seething with conflicting impulses toward new customs and the old, but is in fact a land of ghosts that freely intermingle with the inhabitants of this world. The people in Boehm's stories live in a world where the boundaries are quite fluid, and unseen things come straight into view and say the unspeakable. Characters in these stories suddenly find that all the people around them have an eggshell surface in place of a face, o

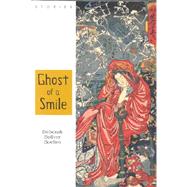

Ghost of a Smile

by Boehm, Deborah BoliverRent Book

New Book

We're Sorry

Sold Out

Used Book

We're Sorry

Sold Out

eBook

We're Sorry

Not Available

How Marketplace Works:

- This item is offered by an independent seller and not shipped from our warehouse

- Item details like edition and cover design may differ from our description; see seller's comments before ordering.

- Sellers much confirm and ship within two business days; otherwise, the order will be cancelled and refunded.

- Marketplace purchases cannot be returned to eCampus.com. Contact the seller directly for inquiries; if no response within two days, contact customer service.

- Additional shipping costs apply to Marketplace purchases. Review shipping costs at checkout.

Summary

Table of Contents

|

7 | (30) | |||

|

37 | (18) | |||

|

55 | (20) | |||

|

75 | (26) | |||

|

101 | (58) | |||

|

159 | (42) | |||

|

201 | (54) | |||

|

255 | (32) | |||

| Epilogue | 287 |

Excerpts

Chapter One

THE SAMURAI GOODBYE

It is a melancholy truth that even

great men have their poor relations.

--Charles Dickens

Bleak House

Sometimes I imagine him walking these silent sloping streets in his beaver hat and caped greatcoat, trailing his long sepia-ink-stained fingers over the rough stone walls of embassy mansions and robber-baron estates. My grandfather, the genius--writer, painter, translator, polymath, president of the Asiatic Society, lover of women, collector of erotic ghost stories and supernatural netsuke . I never met the man; I know him as you do, from daguerreotype and anecdote, from biography and tribute, from that tacky TV docudrama, from his astonishing heap of work. And now here I am, following in his footsteps in the physical sense, at least: strolling the same slanted streets, reading the same inscrutable walls with my fingertips, trying to figure out what drew me back to Tokyo when I'm supposed to be drift-diving in the southwest Pacific, immortalizing the gaudy, gauzy lives of nudibranchs for a glossy new nature magazine.

"Any relation to the great man?" people ask, when they hear my name. I always used to answer "Yes," proudly, "I'm his grandson."

Then, a few years ago, people began looking at me askance as if to say, "At your age he had already published ten books and divorced five wives; what have you done lately?" Or else they'd turn coy, trying to show how well they knew the great man's quirks. " Saraba ," they would say in parting, for that was one of my grandfather's idiosyncrasies, or affectations; he never said sayonara , preferring to use the raffish feudal form of farewell. I've never found the time to visit his grave, but I gather that's all there is on his tombstone in Yotsuya Cemetery: his name, the dates, and that elegant, archaic goodbye.

So, you're wondering, what have I done lately? Well, at the moment I'm a grad-school dropout in academic limbo: D.I.P. (Doctorate in Progress) or, more accurately, D.I.S. (Doctorate in Stasis) or, better yet, D.I.D. (Doctorate in Disarray). I suppose I could still go back and resume work on "`Bespectacled Dwarves': Japanese Self--Image from the Edo Period Through the End of the Twentieth Century." The academic door remains open but the crack is growing smaller every day, as is my desire to return to that world of footnotes, backbiting, and hasty lunches of rancid falafel in Westwood Square. In the meantime, I support myself by hired-gun photography, filial freeloading, and the occasional raid on my inherited stock portfolio. I sometimes think I might like to be a writer; the trouble is, that's already been done.

I don't even have a steady girlfriend at the moment, much less a wife (or five), and unlike my larger-than-life forebear, I'm not six foot eight (but where I grew up--L.A., London, Tokyo, Rome--six-three wasn't such a disgrace). Nor is anyone likely to describe my face as "a devastatingly handsome cross between Apollo and the Dark Angel" (and a posthumous pox on the dizzy self-published poetess, one of my grandfather's extramarital conquests, who coined that pukish phrase). Those are just a few of the reasons why now, when Old Tokyo Types prick up their ears and say, "Oh? Any relation?" I shake my head and sigh, "No, alas, I'm afraid not. It's quite a common name in England, you know."

I have a letter in the pocket of my brown leather jacket as I walk the dark, diagonal streets on this chilly indigo night. The paper has the feel of old papyrus or mummified skin: dry, tissuey, barely clinging to molecular coherence. The stamps are wonderful and valuable too, no doubt. One is a reproduction of Tomioka Tessai's Bodhidharma Riding a Tiger , while the other shows Meigetsu-in, the hydrangea temple in Kamakura, in full flower, huge frothy billows of pink and blue like a baby shower gone berserk. The postmark is Karuizawa, the date is September 30, 1968, and the envelope is sealed with a fissured clump of wax the lusterless cinnabar color of old Chinese screens. (Sealing wax was another of my grandfather's stylistic furbelows, although I don't believe he ever went so far as to sport a pseudo-aristocratic signet ring.) The letter is addressed to my father, T. O. Trowe, Jr., and it is signed, of course, Saraba . This brittle piece of paper is my only portable keepsake of my grandfather, or my father, and I must have read it a hundred times. I know it by heart or, as the Japanese might say, I know it in my guts.

Third paragraph down, loopy scratch of sepia ink: One thing I regret, as I near the end of this immensely interesting incarnation, is that I have never had an intimate encounter with the supernatural nuances of the night in Japan. The uncanny, yes, the enchanted, to be sure. But I never saw a footless ghost, I was never accosted by a tanuki- goblin masquerading as a priest, I was never seduced by a comely fox-woman with a bushy russet tail beneath her voluminous skirts. Fortunately, I believe in metempsychosis, so I can say with a blithe and hopeful spirit: Maybe in my next life .

Poor Grandpa. The women flung themselves at his size-fourteen feet, the men worshipped the tatami he walked on, but the Japanese ghosts wouldn't give him the time of ... day.

* * *

Thinking those thoughts and a great many others, I started across an unlit bridge in the Akasaka district of Tokyo. The dragon-posts and arabesque embossing reminded me of Sacheverell Sitwell's description of the Bridge of the Brocade Sash, and I began to wonder what it would be like to be a not-quite-genius grandchild in that other gifted, flamboyant family. "Nobody comes to give him his rum/But the rim of the sky/Hippopotamus-glum," I recited out loud, and I didn't notice the woman crouching at the other end of the bridge until the sound of her crying roused me from nay reverie.

I couldn't see the woman's face, but I could tell by her gold-buckled pumps and the cut of her gray wool coat that she was, as my class-conscious mother or my grandfather's immortality-rival Lafcadio Hearn might have put it, from a good family. A long loose sheaf of blue-black hair hid her face, and she was weeping helplessly, as if she had been walking across the bridge and had suddenly been overcome by grief or despair.

"Excuse me, Miss, are you all right?" I asked. The woman made no response, and her crying seemed to increase in volume. "Are you all right?" I repeated, using extra-polite verb forms so she wouldn't mistake my intentions. "Can I be of any assistance?" I could tell from the curve of her back and the shine of her hair that the weeping woman was young, and probably pretty, too. Maybe I would be able to cheer her up over a cup of tea or a glass of beer, and after that, who knew? Passion born of sorrow could be a beautiful thing.

Still the woman sobbed, and hid her face. "Please don't cry," I pleaded, but the woman just hunched her slender shoulders and wept some more. Maybe I should give up, I thought. My knees had begun to cramp from crouching for so long, and I stood up and stretched. "Are you sure I can't help you?" I asked, one last time.

Suddenly the woman stopped crying. Raising one small white hand, she pushed back the shimmering curtain of hair and lifted her head to reveal a face that was completely blank and smooth, like an egg. She had no eyes, no nose, no mouth, no features of any sort. I stood poleaxed with shock and disbelief for a few seconds, while the rational part of my brain posed logical questions like, "How could she cry without a nose, or a mouth?"

After a moment my mind made the transition from logic-fueled denial to unreasoning fear. I let out a shrill girlish half-shriek, then ran away as fast as I could, which, since I used to win schoolboy medals in both cross-country and the 440, was very fast indeed.

I ran for blocks, I ran for miles. I sprinted through dark secretive sweets, past blue-roofed temples and vermilion shrines and topiary parks, past garden estates and fluffy-plastered condominiums, past gas stations and "convenience stores," now inconveniently closed. I saw no one along the way--no insomniacs out walking their miniature dogs, no night-shift joggers, no cruising taxis.

Please God, I prayed in a secular, opportunistic way. Please let there be someone to talk to, soon.

No more than thirty seconds later, I saw a light up ahead under a golden-leafed gingko tree. I slowed to a trot, and as I drew closer to the light I saw that it was an oil lantern, illuminating the stall of an itinerant noodle vendor. It struck me as an odd, untraveled place to set up a soba stand. At this time of night, most vendors were plying their trade outside train stations or in lively drunkenness-and-debauchery districts like Shinjuku and Yurakucho. Still, it was a godsend. (Thanks, God, I thought. I'll give you a jingle next time I need a favor.)

Alfresco food stands were among my favorite things in Japan, along with deep-mountain hot-spring baths, shrine maidens in long crimson culottes, and the mesmerizing sound of monks chanting mystic syllables behind crumbling snuff-colored walls. I also liked beer in amber bottles, salty seaweed crackers, the bitter salutary foam of ceremonial tea, and buckwheat noodles in any form at all.

" Konbanwa ," I said as I ducked, still panting, under the calligraphed muslin curtains and sat down on a wobbly wooden stool.

"Good evening," said the vendor, with a friendly gold-toothed smile. "You look as if you've seen a ghost!"

"I don't know if it was a ghost," I said. "But I definitely saw something ." The noodle man opened a long-necked bottle of beer and handed it to me, then busied himself behind the counter, scraping the cast-iron grill with a spatula, pouring a pellucid puddle of oil and spreading it around before adding chopped cabbage, carrots, and onions. When the vegetables were soft and slightly charred, he stirred in the precooked buckwheat noodles, scooped the steaming yakisoba onto a plate, doused it with a sweet thick soy-based sauce, sprinkled flamingo-pink shredded ginger and powdery green seaweed on top, and set the plate on the wooden counter.

"There you go," he said, flashing his gleaming dental work again.

" Itadakimasu ," I said, signaling for another cold amber bottle of Kirin. This is bliss, I thought. Perched on a stool on the edge of a fragile whirling planet, eating simple food, drinking sublime beer, with another human being to talk to or be silent with. The proprietor had been cleaning his griddle with the stainless-steel spatula, singing "Ginza Love Story" in a loud tuneful tenor with all the usual karaoke-balladeer flourishes. Now he leaned on the counter and looked at me with curious yellow-brown eyes.

"Tell me," he said casually, his bald head and metallic teeth glinting in the lamplight. "What was it that frightened you so?"

I took a bite of noodles and a big gulp of beer. Lots of Japanese people still believe in ghosts and apparitions and fox-bewitchment, I thought. This nice chap won't think I'm crazy.

So I told the soba man the story, complete with imitations of the girl's incessant sobbing, for (if I do say so myself) I have always been a rather good mimic. As I approached the denouement, the unveiling of that ghoulish unpunctuated face, my feelings of terror and revulsion returned. "And then she pushed her hair back and showed me ..." I stopped in mid-sentence, reluctant to put that incomprehensible image into words.

The noodle man leaned forward, and his benevolent smile suddenly turned into a menacing leer. " Hé-eh ," he said, baring his gilded teeth. "Was it anything like this that she showed you?" As he spoke he drew his hand over his face, and it became smooth and blank and featureless, like an egg. I screamed, and at that same moment, the light went out.

* * *

When I finally regained consciousness an hour or so later, I was looking up at one of the loveliest women I had ever seen. She was Japanese, with one of those classic pale oval Utamaro faces, medieval eyebrows, and a very modern magenta mouth, and she was dressed in subtle shades of pewter and khaki under a celadon-green smock. It turned out that this celestial vision was my attending physician at the Red Cross Hospital in Minami-Azabu. Evidently I had been found lying unconscious on the sidewalk in a puddle of beer, and taken to the hospital by ambulance, for observation. (The noodle stand and its owner had disappeared, of course, and all the neighbors swore they hadn't seen a soba vendor in that vicinity since the Occupation.)

Because this was my life and not some wishful escapist novel, it also turned out that the stunning doctor was newly married, to an absurdly handsome Japanese neurosurgeon. "Any relation to the great man?" he asked me in obnoxiously fluent English, when we were introduced. I was feeling too weak to fib, so I grimaced and said, "Unfortunately, yes." (Too bad we weren't speaking Italian; I've always loved hissing out s-s-s-fortunatamente .) "Well, saraba!" he said with a patronizing smirk as he left my room, his busy-man beeper abuzz, and then the bile-green door closed behind him.

After I got out of the hospital, I found a small stack of invitations addressed to my absent mother in the post-box of her small but expensive pied-à-terre in Akasaka-Mitsuke, where I was camping out. Art openings, lectures, receptions, strange-foreigner parties. Perfect, I thought. People to talk to.

I went out every night for a week, and when I told a few Japanese people what had happened to me, they all nodded sympathetically and said things like "Oh, how scary!" and "You must have had quite a fright," with no trace of sarcasm or doubt. At a tony soirée at the British Embassy, two solemn Japanese matrons told me that the Japanese word for "eggfaced monster" is nopperabo , and I filed that away under Information I Hope to God I'll Never Need Again. Later that night, after they had been hitting the champagne pretty hard, the same women (now giggling uncontrollably) shared their own personal ghost-encounter stories, whispered behind pale jade-ringed hands. I pretended to be impressed and reassured, but I couldn't help noticing that both yarns sounded suspiciously like borrowings from that classic volume, Tales of Murdered Moonlight , collected, annotated, and brilliantly translated from the Japanese by my ubiquitous ancestor, Thomas Oswald Trowe the Original.

The Americans were considerably more skeptical, and after being greeted with halitotic hoots of laughter from a gaggle of dissolute expatriates, I began saying that I had been hospitalized for anemia: my tiny, vengeful vampire-joke. I did, however, relate the genuine version to my mother when she rang me from her flat in Kensington.

That turned out to be a major mistake, because she insisted on sending me to see a psychiatrist named Neville Ruxton, whom she described in her vague way as "an old chum from Trastevere days, before you were born." Oh my God, I thought (the post-traumatic mind as runaway train), what if my mother had an affair with this slimy shrink? What if he's my real father? What if I'm not the great man's grandson, after all? The thought of being deprived of my deepest anxieties made me feel more anxious than ever.

But Neville Ruxton, as if you hadn't guessed, turned out to be a woman, named after a rich-recluse uncle by avaricious, profligate parents. (I was pleased to hear that the fawned-upon uncle had slyly left all his money to a foul-mouthed African Gray parrot named Dorcas.) When I told Dr. Ruxton about the faceless faces she looked smug and knowing, as if I had trotted in on all fours, furry naked body smeared with porphyric salve, carrying a blood-soaked white rabbit in my mouth and saying between guttural growls and bites of bunny tartare , "I don't know, Doc. I keep having these werewolf dreams."

"I wish every case were this simple," Dr. Ruxton said, manicured fingertips pressed together like the roof-beams of a Sepik River longhouse, the multiple facelifts (Mother's gossip) giving her skin an eerie Mongol tautness across the surgically-implanted cheekbones (gossip ibid .). Then, in a voice like treacle and lye, she pointed out that my story bore a remarkable resemblance to Lafcadio Hearn's retelling of the old folk tale known as "Mujina," and suggested that pretending to have had a supernatural experience was the only way I could make myself feel like my grandfather's equal, or even (she added with a that'll-be-the-day smirk) his superior.

"You've been a big help," I lied at the end of the hour. I wasn't in the mood to explain that I had never read "Mujina," nor did I see any point in spreading the greasy entrails of my second-generation inferiority complex all over the sage-velvet couch and the opulent ecru carpet. Besides, I had a plane to catch.

I jogged back to the flat, packed my motley leather-and-canvas bags, and headed for the Tokyo Interdimensional Space Station, also known as Narita Airport. At the airport bookstore, on impulse, I bought an overpriced paperback of Lafcadio Hearn's Kwaidan , subtitled Stories and Studies of Strange Things . By one of those uncanny coincidences it turned out to contain "Mujina," the story that Dr. Ruxton had obliquely accused me of plagiarizing. (According to my dictionary, a mujina is "a supernatural creature with shape-shifting powers." Naruhodo : Now I get it.)

I read the story in flight, while sipping ginger ale and nibbling Neolithic peanuts, occasionally glancing out my shoebox-window at the amazing diorama of cosmogonous clouds and Fauvist sunsets. Hearn's retold tale was so uncannily similar to what had happened to me that I got full-body gooseflesh, and I began to understand why Dr. Ruxton could have mistaken my account for a neurotic fabrication.

Maybe it was the sacramental sunscape, or the feeling of onmiscicnce conferred by cruising so high above the cumulus curtain, but I had a major multilayered epiphany somewhere between the meal (a piece of halibut that passed all understanding) and the movie (some fireball-ridden absurdity which I watched intermittently with the sound off). I realized that ever since I was very young I've been worrying about being great--or rather worrying about not being great. My half-English, half-American father spent his life in the same futile dither; he died of a mutinous heart and a marinated liver when I was twelve years old, after an aggressively nonacademic but lucrative career in the recording industry in Los Angeles, London, and Tokyo. I realized, too, that from what I've read about my entirely English grandfather he never spent a moment fretting about whether he was going to be famous or rich or revered. He just pursued his own idiosyncratic quests and ended up becoming all of the above, not so much by default as by accretion. And finally, just before I fell asleep, hunched knees-to-chin like one of those poignant fossilized figures at Pompeii, it occurred to me that while I may have had an encounter with the supernatural nuances of the night and lived to tell the tale, I still didn't have the foggiest idea what to do with my own natural life.

* * *

--JOURNAL ENTRY

So here I am on the paradisiacal island of Sandovalle, midway between Vanuatu and Tokelau, living in a funky thatched-hut resort and diving daily with the person who is writing the text to go with my photographs. She's a Tahitian-Irish ichthyomythologist and, as she puts it, "tadpole songwriter," who also happens to be the most attractive woman I have ever seen. (No wonder Gauguin went gaga.) The gold of her body, the gleam of her hair, the arc of her eyes, the curve of her mouth, the swell of her pareu , the velour of her voice, the scent of the flowers she wears even to sleep--everything about her drives me mad with desire and tenderness. How do I know what she wears to bed? I accidentally looked in her window one night as I was passing by: Peeping Thomas Trowe, the Third.

Even her name is a blossom, a cantata of vowels: Tea-ah-ré. (That's Doctor Tiare Teha'amana Faolain-O'Flynn, to you.) She's brilliant, of course, and funny and kind. She brings me roasted breadfruit and mosquito repellent, and last week when I stepped on a sea urchin she ducked behind a palm tree, then returned a moment later, shyly holding a leaf-cone filled with her own warm fragrant urine to take away the sting. She sings all the time, sotto that wonderful voce --one day it was "Moondance," the next a Monteverdi madrigal--and sometimes late at night she puts on a pale leotard and a long sheer skirt and dances on the beach like a dryad, or a devadasi .

Once I caught her staring at me with dreamy dilated eyes, a look I associate with poets on laudanum and women in love, and when I asked what she was thinking about she blushed like a half-ripe mango. Today, a major breakthrough. She asked me to come to her bungalow after dinner to read an article she's writing on seahorse myths, and I'm hoping we'll end up dancing in the moonlight, at the very least.

Incidentally, I'm beginning to think that I should stay away from cities. Not because of the hazards of the urban supernatural, but because pavement is not my sympathetic element. This morning the water was heraldic blue on the surface, malachite-green below. The opisthobranchs were in frilly translucent bloom, and Tiare and I swam for hours among the anemone mosques and brain-coral caverns, exploring the curving sonic highways and invisible-blueprint roads of the ocean floor. Whoever said that a sea is just a soggy desert had it completely backward. Deserts are enervated oceans, and seas are the grand oases of Earth.

On a more carnal note, what can I say about Tiare in neoprene, sleek and antic as an adolescent sea otter, long black hair streaming behind her like Cupomedusae tentacles or squid-ink silk? My carbonated lovesick sighs, her disciplined breath: our bubble-streams mingled as we bent our heads over a scarlet starfish or a pregnant male seahorse. ("The protofeminist nurturer," Tiare said later, with a mischievous smile). Once I almost bumped into a neon chorus line of Flabellinopsis iodinea , so mesmerized was I by the sinuous seal-shape undulating in front of me. I have always thought that a full-length wetsuit, worn by a graceful woman, is more alluring than anything in those Naughty Negligées catalogs that used to show up in my mailbox at UCLA, ludicrously addressed to "Professor Emeritus, or Current Occupant."

One of the many things I like about the ocean is that there are no legendary footsteps to follow in, no gigantic shoes to fill, no archives, no curricula , no impossible expectations. There's just vastness and mystery and color and movement and light, and a constant awareness that wonderment (or death) may be lurking behind every rock. And if that isn't a useful existential metaphor, I don't know what is.

* * *

There was music enough in the trees--the drowsy twitters of kingfishers, flycatchers, honey-eaters, and the small gray birds the natives call leaf-ghosts--but just for overkill I had brought along my portable CD player, programmed to croon "Tell It Like It Is" over and over, sweet bayou soul without end, amen. It was definitely Slow-Dance City, as one of my perennially dateless prep-school roommates used to say with a wistful, spotty-faced leer every time he heard anything even vaguely balladic on the radio.

"Nice," Tiare murmured as we danced a disappointingly decorous foxtrot. "The Neville Brothers, give or take a few siblings." Her eyes were closed, and her Tahitian-gardenia wreath was dizzyingly fragrant under my nose. ( Tiare : her namesake flower.) To my dismay, though, her body wasn't touching mine except for the hands and occasionally the feet, when one of us lost our balance on the sand and accidentally trod on the other's bare toes. I kept trying to pull her closer, to fold her arms behind me and crush our torsos together at chest and groin in the subtle erotic tradition of the American high-school dance, but she resisted with surprising determination, as if I were the designated villain in some YWCA self-defense class.

The moon was full, and the broad silver stripe it cast on the cerulean water looked like a palpable, walkable road. Suddenly I wanted to ask Tiare to walk that illusory path with me, and all the other roads in life as well. In that moon-addled instant I saw getting married as an ultimate solution (World's Tenderest Lover! World's Greatest Husband! World's Most Flawless Father!). On a more immediate level, it seemed to be the only way to get Dr. Tiare Teha'amana Faolain-O'Flynn to stop dancing as if there were a roll of barbed wire between us. But just as I opened my mouth to propose, Tiare said, "Let's sit for a while."

The moment was lost, perhaps forever. As we hunkered self-consciously at opposite ends of a straw mat, instead of "I want to spend my life with you," I said lightly, "I don't know, I still think there's something slightly obscene about living in a climate so idyllic that the native language doesn't even have a word for `blanket.'"

"Oh, but they do," said Tiare, who unlike me hadn't picked up all her knowledge of the local culture from breezy, superficial guide books. "They call it `foreign mat for wrapping a chilly corpse.'"

"Lovely," I said sarcastically. "I'll remember that the next time I'm huddled under the covers in London on a frigid December night, alone and palely loitering."

Tiare didn't laugh, or even smile. She just looked at me, the planes of her extraordinary tropical face limned in moonlight. Eat your heart out, Gauguin old man, I thought.

"Listen, Ozzie," she said, and I saw her exquisite brown throat undulate with a nervous gulp, like a hummingbird chug-a-lugging sugar water. "There's something I probably should have told you a long time ago, but it didn't seem relevant until tonight." I was silent, for I knew that nothing good could ever follow a preface like that.

Tiare plunged ahead. "The thing is, I'm married, and I don't know if it's going to work or not. Right now we're separated--sounds like a Julia Child recipe for some egg dish, doesn't it?--but the truth is I don't know yet whether this particular soufflé is going to fall or not. God, that sounds so glib; metaphors always mess me up. Anyway, it was one of those grad-school romances, you know the kind, intense yet absentminded, and we've had some major problems adjusting to the logistics of life in the real world and the dynamics of a long-distance relationship. I mean, to be perfectly honest, which is to say far more honest than I had intended to be on this particular night, we're pretty much like strangers to each other these days. But we aren't seeing other people yet, although if we were, I'm sure I don't have to spell this out, I mean it almost seemed like adultery just to be dancing with you a minute ago, because I'm starting to feel so, um ... never mind. It's just too soon, and too much, and too scary."

Not a word from me. I was the silence tree, the well of stillness, the mine of speechless ore. Actually, I was trying desperately to think of something sensitive and mature to say, but the only words that came to mind were "Damn! Blast! Bloody hell!" After a long moment, Tiare spoke again and this time instead of an earnest confessional tone, her voice sounded dreamy and trance-like.

"The people who live on this island believe that if you tell a really dreadful story on the first night of the full moon, the long-toothed ghosts will leave you alone for the rest of the month," she said. "It's a sort of preventive magic, I suppose. They call it something that translates very roughly as `storytalk insurance.'"

"Blather in the face of fear," I said flippantly. I was still in shock from Tiare's unexpected revelation, for she wore no wedding ring, and I had chosen to perceive her as single and unattached. As for the hyphenated surname which I had found so fetching, there could have been any number of nonmarital explanations for that alliterative pageant of names.

"Blather? That's an awfully cynical, ethnocentric way to put it," Tiare said, but her tone was light. "So do you want to hear my little horror story. or not?"

"Hey, break a leg," said the World's Most Tender Lover.

* * *

Once upon a time, a long long time ago, on a beautiful island that has since been swallowed up by the waves, there lived a young princess named Deemah who was very much in love with her husband. Riahl was a famous warrior with a gift for wood carving, and between battles, when he wasn't decorating canoes and longhouses, he used to make little birds and animals for his wife's collection. Deemah spent her days gathering wild plants to make dyes for the cloth she wove from fibrous tree bark, and trying to imitate the songs of the brightly-plumed birds on her bamboo flute. In the evening, after the cooking fires had dwindled to small glowing coals, like the eyes of wild animals in the night, the two of them would repair to their sleeping chamber and reinvent the stars. It was a perfectly happy life for both of them, until the tall rough-bearded stranger arrived from another archipelago in his fine canoe of teak and mahogony, with a carved crocodile's head on the bow and a hold full of shiny stones and gold doubloons salvaged from the pockets of drowned Spanish sailors.

The visitor's name was Morro. He was a prince from Deemah's tribe who had been away for many years, and according to the rules of the island he could claim any woman he liked for his bride or his concubine, as long as she wasn't married to a member of the royal family. He looked around the fire at the great welcome feast the chiefs held for him, and he knew right away that he wanted Princess Deemah. There was nothing Riahl could say, or do. He was a great warrior and an accomplished craftsman, but he was not of royal blood.

After the feast Morro took Deemah aside and told her that she had captured his heart. He was a tall handsome man, with many shark's-tooth necklaces and several fine shrunken heads at his belt, but she just looked at him coldly and said, "I love my husband, and even if I were single I could never love a man like you." Morro laughed and his teeth, which were a bright bloody red from chewing betel nut, gleamed in the firelight like the fangs of a many-tailed demon. "What's love got to do with it?" he said, or words to that effect.

After that Morro cornered Deemah every chance he got. He told her of his deepening desire and gave her small gifts: a ceramic jar full of the best sago-grub marmalade, a cap of soft red and yellow feathers, a flute made clumsily by his own hand from a hollow worm-eaten branch. At first his desire was only that, the lust of flesh for flesh, but as he saw how pure and faithful Deemah was, his desire turned to love and he felt that if he could have this sweet, fascinating princess in his sleeping chamber every night, he would need no other concubines. But she refused him again and again, until he grew so angry and frustrated that he threatened to kill her husband while he slept.

Deemah looked at Morro as if he had just made a wise and noble suggestion. "Of course," she said, in her sweet voice. "I should have thought of that. I must confess that I am not unmoved by your charms, but I felt bound by my wedding vows. If you will just kill my husband tonight in his bed, then you and I can be together as you wish." Now, Morro was actually a bit of a coward who had never taken a human life, and the impressive-looking shrunken heads that dangled from his belt had been pilfered from a warrior who died of a heart attack in the forest. (To Morro's credit, he did try to revive the man with mouth-breathing before he stole his trophies.) But like many better and worse men before him, Morro was so inflamed by longing that he agreed to do exactly as Deemah said.

Deemah laid out her plan. She would sleep in her mother's palace that night, so Riahl would be alone in their sleeping chamber, under the mosquito net. She told Morro that Riahl liked to go to bed with his straight, shoulder-length hair wet because he believed that bad dreams couldn't enter a wet head, and Morro nodded in agreement, for he too believed in sleeping wet-headed. This Riahl was a magnificent-looking man, and he sounded like a sensible one as well, but there was no choice. If Morro wanted Deemah, he would have to kill her husband. Morro reached out to stroke Deemah's slightly wavy waist-length hair, which was shiny and fragrant with coconut oil, but she shook her head and pulled away. "There will be plenty of time for that, and more," she said softly.

That night Morro sharpened his virgin sword, which had never tasted human blood. At the appointed hour he crept into Riahl and Deemah's sleeping chamber. It was very dark, but he lifted the mosquito net and groped around on Riahl's pillow. Just as Deemah had said it would be, the shoulder-length hair was wet. Morro felt heartsick at what he was about to do to the innocent Riahl, but then he remembered the look in Deemah's eyes when she said, "There will be plenty of time for that, and more." With one great blow, he hacked off his rival's head. It was surprisingly easy and unexpectedly elating, and he felt as if he had finally grown into his manhood. He would put Riahl's handsome head in the smokehouse and when it was shriveled and shrunken to the size of a baby coconut, he would hang it on his waistband, to show the world what he did for love.

Carrying the dripping head by its hair, Morro walked down to the beach, where Deemah had promised to meet him. The severed head left a trail of blood along the pristine white sand, but it was a moonless night and Morro didn't notice. While he was looking around for Deemah, a man jumped out from behind a palm tree, holding a fiery torch in one hand and a gleaming pearl-handled sword in the other. Morro screamed, for the man with the torch looked exactly like Riahl. Then he looked down at the head that hung from his hand and screamed again because the bloodied face bore the unmistakable flower-like features of Princess Deemah: the woman he desired, admired, and loved. Riahl and Morro sat down on the beach and wept like brothers, banging their heads together in grief, and then they pieced together the story, bit by bit.

When Morro threatened to kill Riahl--a threat he had not at first had any intention of carrying out--Deemah had evidently decided to substitute herself in order to save her beloved husband's life. She told Riahl to stand watch down by the beach with his sword at the ready, because (she fibbed) the royal witch doctor had told her that a certain three-headed sea demon was going to sneak ashore that night and suck the blood of all the villagers. Riahl was very superstitious, so he readily agreed. Then Deemah hacked off her glorious hair, wetted it to conceal the difference in texture, and lay down to wait for Morro's sword.

"You can kill me if you like," Morro said, grabbing Riahl's blade and holding its sharp edge against his throat.

"No," said Riahl, heaving the sword down the beach as jar as he could. "More killing will not bring Deemah back. I will treasure her memory, and perhaps, because men are men, I may even marry again someday, but no one will ever take the place of my darling Deemah. She was the love of my life, and I don't blame you for wanting her, too."

Just then a sentry came along, and Morro tearfully confessed to the inadvertent murder of Princess Deemah. The sentry wasn't certain whether it was a crime for one member of the royal family to kill another, even inadvertently, and while he went to rouse the tribe's magistrate from his bed of shinyti leaves, Morro got to his feet and gave Riahl a double-forearm embrace. Then he went down to the shore, climbed into his splendid canoe, paddled out into the dark ocean, and was never seen again. Some say the sharks got him, but there are those who still insist that Morro lived out his life on some lonely treeless atoll, a wild-haired, deranged monk ranting at the seagulls and chanting with the clams.

Deemah's severed head was buried with her body, but a year after the murder her grave was opened and the skull was removed so Riahl could place it on his household altar along with his dead wife's flute, her hand-dyed robes, and all the bird and animal carvings that she had treasured so. Riahl never married again, but they say that he could be seen down at the beach on every full-moon night, dancing with a woman who would have been beautiful if she had only had a head.

This is a very ancient story, and I have told it to you exactly as it was told to me. May the gods bless your human spirit, and may your nights be free from ghosts.

* * *

It was just past midnight when Tiare finished her mesmerizing monologue, and the enormous moon above us was like hammered platinum, or silver mixed with gold. It illuminated the deserted beach with a light that was brighter and more naked than daytime, an X-ray polygraph light that made it impossible to tell a lie.

"I love you, Tiare O'Flynn," I said. I looked at her shining storyteller's face and wished I had brought my camera, and then I thought, No, I don't want a grimy lens between me and this perfect (which is not to say painless) moment.

"Earth to Ozzie," Tiare said, and I realized that I hadn't said "I love you" out loud, after all. In fact, I hadn't said anything, which was downright rude.

"That was a brilliant story, beautifully told," I improvised. "And quite startlingly relevant to us, tonight."

"Your turn," Tiare said. "One good fright deserves another." I've never been terribly good at command performances, and my mind went immediately, utterly blank. I thought of telling Tiare about my bizarre experience in Tokyo, perhaps defusing its power a bit by putting it into the third person ("Thomas Oswald Trowe the Third was walking across an unlit bridge ...") or even by pretending it had happened to someone else ("One night after midnight, a man was hurrying up the Kii-no-Kuni Slope when he perceived a woman crouching by the moat ..."). But even though I was prepared to promise to cherish Tiare forever, on the spot, I wasn't quite ready to deal with her possible ridicule, or disbelief.

"Hey, strong silent type," Tiare said, nudging me in the side. She seemed to have crept closer to me on the mat, or maybe I had unconsciously drifted toward the middle. "Are you going to tell me a scary story, or not?"

"Sorry," I said disingenuously. "I don't know any scary stories. I'm afraid I'm going to have to tell you a nice story instead."

"That's not fair," Tiare complained, but as she settled down to listen her bare arm brushed against mine, and she didn't take it away. I swallowed, and took a deep breath.

"Well," I said in what I hoped was a normal tone of voice, "this is something I saw on a newsreel on Japanese television a few years ago, and it really impressed me. It was a three-minute feature about a man--he must be close to seventy now--who has taken over a hundred thousand photographs of Mount Fuji. Twenty years ago he closed his photo-developing shop in Tokyo and moved to a town near the foot of the mountain so he could photograph it every day. That's his self-assigned full-time job: taking pictures of that one enchanted mountain. He leased a plot of vacant land at the base of the mountain, and he plants it with seasonal flowers and then uses the blooms as a foredrop, if that's a word, for his portraits of the mountain. Every morning he gets up at two A.M., puts on his beret, and drives to the foot of the mountain. Then he sets up his tripod and waits for the pictures to compose themselves.

"Anyway, he has made some extraordinary photographs, just staggeringly true, beautiful images. I remember one of a thousand cranes in frozen flight against the mountain, and another taken from one of the lakes at the bottom of Mount Fuji on a full-moon night, with the moonlight making a squiggly golden line from the shore to the oar of a rowboat, and another shot of the mountain looming above a riotous profusion of yellow flowers with the sky above filled with soft puff-pastry clouds, like a lemon-meringue sky, if lemons were blue. And at the end, the photographer said that when he went to live near Mount Fuji he destroyed all the slides he had taken in the twenty preceding years, and now he was thinking it might be time to destroy the hundred thousand pictures he's taken since then, and start over from scratch. The interviewer said, `But why do you do this? Why this single-minded devotion to the image of one mountain, when we live in such a wide world filled with so many marvelous and photogenic things?' And the photographer shook his head and said, `I don't know. You might as well ask the mountain.'"

Now it was Tiare's turn to be silent. The birds had finally gone to sleep, and the only sound was the rustling surf and the faint far-off shouts of some night fishermen diving for lobsters beyond the reef. "That's a wonderful story," she said after a long, electrified moment. "And you're a wonderful man." As I leaned toward her she jumped to her feet, thus saving me from the unpardonable gaffe of kissing a technically-married woman who was clearly dying to be kissed.

"What about you, Thomas Oswald Trowe the Third? Where do you go from here?" Tiare asked, looking down at me with her eyes strangely bright and her rippling river of black hair agleam with auburn highlights. She could have been Deemah the Princess, before she lost her head.

"I don't know," I said slowly. "I guess I'll just keep blundering along until I find my mountain."

"Good man," Tiare said approvingly. Then she added, suddenly playful and flirtatious, "Last one in the water's a rotten mongoose egg!" She sprinted down to the shoreline, shedding her hibiscus-patterned pareu as she went.

"Hey, wait," I called. I scrambled to my feet and followed her, stumbling out of my clothes as I ran, but by the time I hit the water Tiare was already in the midst of the silvery stripe of moonlight, draping her long wet hair over her breasts like Botticelli's Venus and beckoning me to join her on that shimmering mirage of a road.

* * *

I wish I could end it there, leaving you to think hot love and happily ever after, but I'm beginning to think I'm not what the Japanese would call a " happii endo " kind of guy. There was something strange going on, some trick of moonlight or imagination, and when Tiare raised her face to me it appeared suddenly smooth and uninterrupted, like a giant hard-boiled dinosaur egg. It was an optical illusion, of course. I knew that even as I screamed.

After a moment the lineaments of light shifted and her face returned to its beauteous human state, but the scream was already out, hanging in the dangerous air between us like a Damocles' sword of sound. I tried to explain, stammering out the whole unlikely story of that occurrence on the bridge in Tokyo, but the spell was seriously sundered. When I tried a cautious post-confession kiss, our lips felt rubbery and cadaverous. Tiare's mouth was tightly closed, and her arms were crossed upon her naked chest in classic noli-me-tangere body language: I am a female fortress, and my moat is filled with crocodiles .

"I may drop you a line after I sort things out with my husband," she said the following day as we stood on the steaming tarmac waiting to climb onto our respective cartoon-mouse airplanes (built, someone said, by two brothers in Dublin--Roy, I speculated, and Walt). It was not a long goodbye, just an awkward peck at the corner of that shapely mouth, a dizzying whiff of ginger from a farewell lei, a million unsayables left unsaid. Our second kiss, I thought morosely. And probably our last one, too. My heart was a sour heavy stone, my stomach a ferris wheel gone berserk. I tried to think of something light and curative to say ("Sorry, I had a Julia Child moment and accidentally mistook you for an egg dish" or maybe a Grouchoesque "You're certainly the dishiest egg I ever saw!"). In the end, though, I stuck with silence.

Tiare boarded first; there was a sign above the door of her aircraft that read THANK YOU FOR NOT SMOKING. She looked back at me and blew an unbearably ironic kiss off the tips of those fantastic golden fingers. "Thank you for not screaming," she said, and then she was gone.

(Continues...)

Copyright © 2000 Deborah Boliver Boehm. All rights reserved.

An electronic version of this book is available through VitalSource.

This book is viewable on PC, Mac, iPhone, iPad, iPod Touch, and most smartphones.

By purchasing, you will be able to view this book online, as well as download it, for the chosen number of days.

Digital License

You are licensing a digital product for a set duration. Durations are set forth in the product description, with "Lifetime" typically meaning five (5) years of online access and permanent download to a supported device. All licenses are non-transferable.

More details can be found here.

A downloadable version of this book is available through the eCampus Reader or compatible Adobe readers.

Applications are available on iOS, Android, PC, Mac, and Windows Mobile platforms.

Please view the compatibility matrix prior to purchase.